Toggle Search Search Close

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Clear all personalization

Science and art are often regarded as distinct – either a person can’t be serious about both or an interest in one must relate somehow to work in the other. In reality, many scientists participate in and produce art at all levels and in every medium.

Here are just a few of these people – students and faculty – who study the sciences at Stanford University but also take part in the arts, both professionally and casually. From first-time dancers to life-long painters, these scientists give us a glimpse into the many ways science and art intersect.

Image credit: Kurt HickmanHideo Mabuchi grew up in a culture that values traditional craft and began collecting it himself during his travels. So, although he began making ceramics on “a bit of a whim,” it was another way of engaging with what he’d long appreciated. As for being a physicist to boot, Mabuchi has always had broad interests.

“I remember going to college thinking maybe I would do economics or aeronautical engineering, and I had a period of deep interest in linguistics and philosophy,” he said. “In the end, I really liked the activity and community I found in physics.”

Getting into wood-firing solidified Mabuchi’s devotion to ceramics. Intrigued by the transformation of uniform, bare clay into a riot of colors and textures, he has made many hundreds of wood-fired pieces, built his own blown-ash kiln on campus and studied the physical and chemical process of wood-firing using electron microscopes at the Stanford Nano Shared Facilities. He has recently curated several displays at Stanford, including a gallery of his electron microscope images and an exhibition of East Asian ceramics. During his residency at the Haystack Mountain School of Craft two years ago, Mabuchi started loom weaving. Some of his recent work combines clay and textiles.

For undergraduates, Mabuchi teaches a course on ceramics, physics and the creative process. He feels that teaching at this intersection is an opportunity for him to contemplate broader questions about “meaning and meaning-making,” while also showing students that science and art aren’t mutually exclusive.

“It’s very natural to have interests both in artistic pursuits and in scientific ones,” he said. “And it’s great for those of us in the sciences, engineering, math who are interested in pursuing art to make ourselves visible to our students … to provide a role model of that and to give each other permission to do that.”

Image credit: Kurt Hickman Share this cardKalanit Grill-Spector standing in front of four of her paintings holding a paint palette and paintbrush

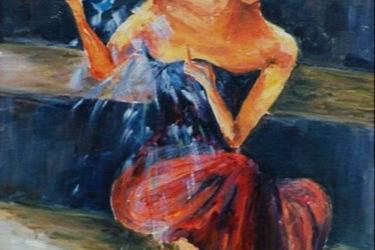

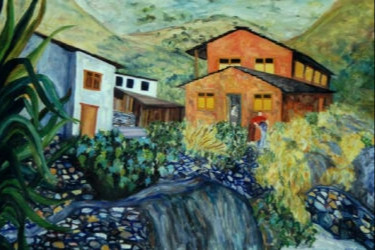

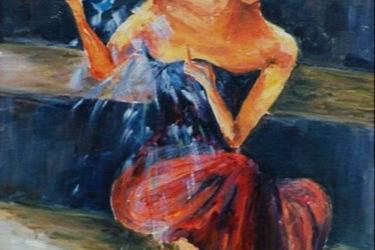

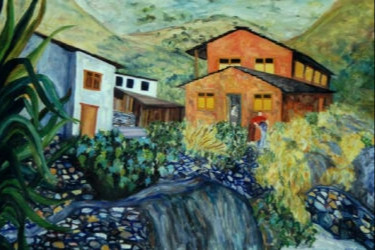

Image credit: L.A. CiceroPainting and drawing were always a part of Kalanit Grill-Spector’s childhood. But it wasn’t until college, when she was looking for a mental escape from her engineering classes, that she began taking formal art classes. “I really enjoyed the intellectual part of engineering but I needed a more creative outlet,” she said. She continued taking art classes throughout her undergraduate and graduate education.

With bold colors and thick lines, Grill-Spector paints vivid images of people, animals and scenes. She describes her art as expressionism. “I don’t try to be precise. It’s more emotional and helps my mind both wander and concentrate,” she said.

Grill-Spector was originally intent on becoming an engineer but found she was more interested in computations. She shifted her focus to computer vision, which then led her to neurobiology, where she ended up modeling the brain using her computer skills. Now, as a cognitive neuroscientist, professor of psychology and member of the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute at Stanford and Stanford Bio-X, she studies how visual recognition works. “I think I have a really good visual understanding of things, and that’s why I like painting and why I like studying vision,” she said.

Grill-Spector finds there is a clear relationship between understanding art and being able to communicate science effectively. “Having good visuals really helps convey ideas and information in a clear way – it’s a really good way to get people to understand your idea,” she explained. This is one of the reasons she incorporates an art project into the curriculum for her undergraduate class, Introduction to Perception. For their final assignment, students build or draw an illusion. Grill-Spector said she enjoys witnessing the creativity of her students and seeing how they relate art and science. “They’re both really creative processes,” she said.

By Kimberly Hickok

Image credit: L.A. Cicero Share this card

Alice Lay sitting at a counter with her art supplies, various kitchen objects are in the foreground to the left

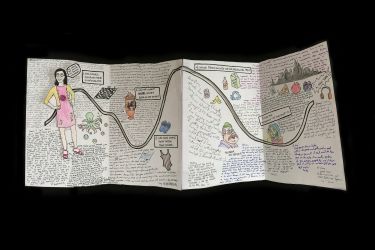

Image credit: L.A. CiceroAs a young girl, Alice Lay would find ways to incorporate an element of crafting into her class assignments. “I was always the one who would do more than the teacher asked,” she said. She once purchased an expensive wood burner just to create designs on an art piece she wanted to incorporate into her history class project.

Lay returned to her artistic roots as an undergraduate at the University of California, Berkeley to make personalized thank-you cards for her professors. She enjoyed making the cards so much that now, as a graduate student in Jennifer Dionne’s lab, she continues the practice for members of her research group – but she’s taken it up a notch.

“Now, as I work on them, I get more and more crazy ideas like, I can make this flip up or this light up,” she said. Recently she incorporated tiny electronic LED bulbs that light up on the card when you press three small buttons. For another card, she wrote hidden messages in invisible ink.

While creating cards is her main artistic medium, she enjoys finding creative ways to make her scientific data more visually appealing. “I find that to be really nice because I can use my artistic skills for my papers and my presentations, and be creative on that point,” she said.

But crafting cards also serves as an escape from her science career, she said. When experiments are failing and troubleshooting isn’t working, she feels stuck and frustrated. “But my cards are feasible,” she said. “The mechanics aren’t very complicated so I feel like whatever I can think of is doable.”

Every card she makes is unique to the person she’s making it for. She includes things like an image of the person in a favorite outfit and references to inside jokes. “It’s always fun to incorporate those because I think it’s so much more personal,” she said. “And it’s my way of thanking them for influencing my life.”

By Kimberly Hickok

Image credit: L.A. Cicero Share this card

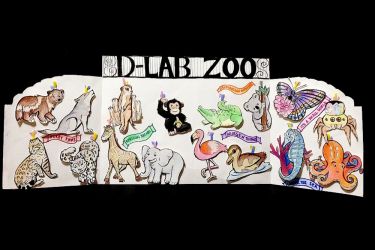

Like many people, Meredith Fields was introduced to art as a toddler. That was when she began drawing and working with watercolor – and she never stopped.

“Back when I was in school, I was always known as the ‘artistic kid’ and it really wasn’t until I got into college that I decided to even try science,” said Fields, a graduate student in chemical engineering at Stanford, who added papercut art to her repertoire in high school. “I wanted to do something that was practical but also I wanted to take the one chance I had at college to try my hand at something technical and become qualified at that.”

Fields’s first internship was at NASA designing aerogels for the thermal protection of space probes and other instruments. She then worked on battery technologies. As part of the Nørskov lab at Stanford, she currently uses computational models to assess the efficiency with which different catalysts assist chemical reactions.

Although Fields imagines possibly combining her art and her science in the future, she purposely engages in them separately for now.

“There have been phases of my life where I go in and out of art and, especially being a graduate student, it’s hard to manage your time in a way where you can continue to pursue art,” Fields said. “So, what art means to me has changed over time. Right now, it’s my stress release. It’s my way of thinking in a way that’s not math or equations.”

Fields said that the more she talks about her dual interests in art and science, the more she meets others who have similarly varied pursuits. Even for those who feel exclusively drawn to science, she encourages further exploration of art, believing that it touches everyone’s lives and there is something for everyone to appreciate in it.

Image credit: Kurt Hickman Share this card Susan McConnell photographing a moose Image credit: Tim GramsAs a child, Susan McConnell remembers rifling through National Geographic at her grandparents’ home and coming upon an article about Jane Goodall’s chimpanzee research in Tanzania. Goodall’s work looked exciting and exotic – and quite glamorous – and it opened up a world of possibilities for McConnell. “I became completely and romantically enamored with the idea of being out in Africa with wild animals,” recalled McConnell, a professor of biology at Stanford University. “I’d always been an animal-crazy kid, and the idea that you could study animals scientifically was what drew me into science.” That article eventually led to two careers for McConnell: one as a neurobiologist and another as a conservation photographer.

Her early efforts to study animal behavior in the laboratory led McConnell to focus on solving the fundamental mysteries of the genes and cellular mechanisms that form neural circuits, which are the underpinnings of all behavior. She was more tentative about pursuing photography until a moment in 2005, when she was photographing a polar bear jumping across ice floes in the Arctic north of Norway. Although she was freezing cold, she realized that it was the happiest she had ever been.

“In wildlife photography, there are often hours of just sitting and waiting. Then, all of the sudden, two, three herds of elephants come to a watering hole and you have two cameras out and everything is happening,” said McConnell. “Those moments where everything comes together, the moments that make an image really special, are very rare.”

In addition to her biology classes, McConnell teaches an IntroSem on conservation photography and runs a year-long capstone project where seniors in the natural sciences express science through art. She was also the first non-art faculty member to have a show – on elephants and the ivory crisis – in the Stanford Art Gallery.

And, like Goodall, her work has been featured within the pages of National Geographic.